City Travel – Rampur, Uttar Pradesh

200 km from Delhi.

[Text and photos by Mayank Austen Soofi]

In the Shikargah, two derelict brick pavilions face each other across a fish-stocked pond observed by mango and jamun trees. “On this one sat the nawab sahib hunting for fish,” Mehboob Shah Khan, the pond’s watchman, says. “On the other sat his begum.”

Close to the edge of the water sits a hunting lodge, with carved ceilings and a sloping tin roof. Some of the windowpanes are missing, and the wire mesh crumbles to dust at a touch.

The pond, the lodge and the nearby Khas Bagh, a 100-room palace, belong to the son and daughter of Murtaza Ali Khan, the last titular nawab of Rampur, a former princely state in Uttar Pradesh (UP), 200 km from Delhi. The inheritance, which includes other scenic buildings and orchards—even a private railway station—is being contested by a multitude of cousins in the Supreme Court.

Sitting in her parlour in Delhi, the nawab’s daughter, Naghat Abedi, explains to The Delhi Walla in her forceful voice that while her grandfather, Raza Ali Khan, was Rampur’s last ruling nawab, her father held only the title after the state’s formal merger with India in 1949 stripped royalty of their powers. “The custom was that the nawab’s eldest son, who was recognized as the new ruler of Rampur, inherited the property. In 1971, the law changed and the Union government withdrew the privy purses of the royals and their titles were abolished. My father was derecognized as the nawab of Rampur, but our private properties remained with him. However, his eight siblings went to court demanding that they too should be given the right to his property, according to the Muslim law of inheritance. In 2002, the Allahabad high court gave us a favourable verdict. The Supreme Court will deliver the final judgement.”

Abedi’s brother Mohammad Ali Khan, who would today have been the nawab if the old ways had survived, lives in Goa. “The high court has given us the possession of our property but we are not allowed to make any changes until the final verdict,” says Mohammad on phone from his home in Panaji. “If the Supreme Court verdict comes in our favour, a lot can be done with the Rampur property. At this time it’s not appropriate to discuss future plans but do remember the bloodline has the same vision, energy and determination that made Rampur a model state.”

Meanwhile, as the political influence of the nawabs is being challenged, their charisma waning and their sprawling palace almost in ruins, a certain allure still clings to the name, for their former state holds a symbolic place in the idea of India.

Rampur is special for a number of reasons. It was the first princely state to accede to the Indian union. Its first parliamentary representative was the freedom fighter Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, who in October 1947 famously exhorted the Muslims at Delhi’s Jama Masjid to “pledge that this country is ours, we belong to it and any fundamental decisions about its destiny will remain incomplete without our consent”. Unlike neighbouring Moradabad and Bareilly, Rampur, a district with the highest Muslim proportion in UP (49.14%, according to a report of the Sachar Committee), has never witnessed a major Hindu-Muslim riot, not even in the aftermath of the Babri Masjid demolition in 1992. Rampur also has the distinction of being the only place aside from Delhi’s Rajghat to preserve Mahatma Gandhi’s ashes.

“The nawabs were the symbols of Rampur’s Ganga-Jamuna tehzeeb, its peaceful Hindu-Muslim coexistence,” says historian and advocate Shaukat Ali Khan, author of the voluminous Rampur ka Itihas. “The Muslim rulers were tolerant towards other religions and employed Hindus in senior administrative posts. One nawab (Raza Ali Khan) even composed poems in Bhojpuri for Hindu festivals like Holi.”

Rampur has also shaped the country’s cultural heritage. A patron of some of India’s great artistes, including ghazal singer Begum Akhtar, Kathak maestro Acchan Maharaj and the last direct descendants of the legendary Tansen, the Rampur court gave Hindustani classical music its Rampur-Seheswan gharana (school). The court also patronized poets such as Mirza Ghalib and Daagh Dehlvi. Khas Bagh presently houses the poet Gulrez. A favourite of Murtaza’swife, he lives alone in the palace with his family. “After her mother died in 1993, Naghat Begum entrusted to me the care of Khas Bagh,” says Gulrez, 62. Possessing a quiet demeanour, he supplements his income by composing songs for TV serials on Doordarshan. He says: “There could be djinns here, but I’m not scared. When the muse strikes me, I pen ghazals in my room.”

Khas Bagh is situated at a distance from the fort where the nawabs originally lived. Built in stages in a jumble of late Mughal and British architectural styles, when it was completed in 1930 it was the first palace in India to install an air-conditioning unit. In his book, The Princes of India in the Endgame of Empire, 1917-1947, Ian Copland reports that when Lord Mountbatten visited Rampur, he likened the palace to “a New York hotel”.

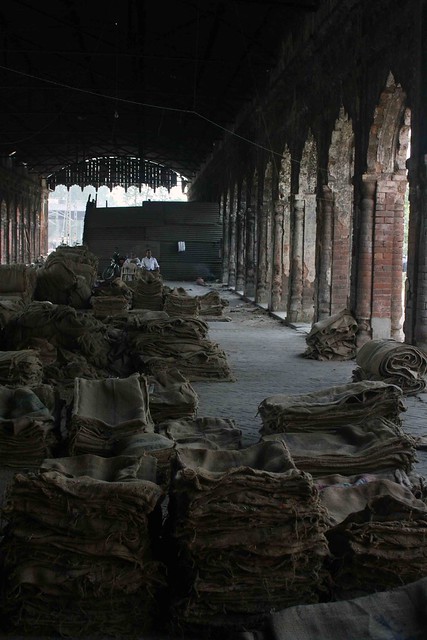

Today, most of its rooms are locked, and its bare corridors are dark. The Belgian glass chandeliers have lost their sheen. The Burma teak panelling is losing its hold on the neglected curved ceiling. The carpets have been rolled up and stowed away in plastic sheets. One room is lined with dusty portraits of the nawabs, while a dead cockroach lies on the dining hall floor beside enormous paintings of the French countryside. A stuffed tiger lurks by a marble staircase. Bats cling to the eaves. A noticeboard outside reads: “Ghoomna Mana Hain(Trespassing not allowed)”.

Making his presence felt through his imposing physicality and stern expressions, Salim Ahmad Khan, aide-de-camp of Murtaza, is standing in the reception of what used to be the palace’s guest block. He reminisces: “The kitchen had specialized cooks. Haider Khan could make two types of rice dishes in a single cauldron. Aziz Khan was an expert in shab deg. Laddan Mian made sweets such as dar behesht. Zameel Khan was trained in English food. Shaukat Bhai was a baker who once made a birthday cake in the form of a palace, complete with electric lights. Some of these cooks ended up at Rashtrapati Bhavan in Delhi and some in the royal kitchens of Saudi Arabia.” The 72-year-old man pauses. “Democracy is fine but the nawabs knew how to talk. Nowadays people elect paanwallas as their rulers.”

A 5-minute drive from the palace is Noor Mahal. Formerly the residence of the British representative in Rampur, this white colonial-style bungalow is occupied by Begum Noor Bano and her son Kazim Ali Khan, one of the parties in the property dispute. They are the political inheritors of the nawabs.

Begum Bano is the widow of Zulfiquar Ali Khan, aka Mickey Mian, the younger brother of Murtaza. The nickname was for the convenience of his British nanny, who had difficulty pronouncing his name. “Mickey Mian was the last of the great men of the nawab family,” says historian Shaukat. “He was extraordinarily honest and had a great connection with the people. He was elected four times to represent Rampur in Parliament.”

Early in 2012 his son Kazim was elected to UP’s legislative assembly from Suar Tanda, a rural constituency in Rampur district. Relaxed, he initiates chit-chat through the medium of the latest Bollywood hits. “When Mickey Mian died in a road accident on the day of Eid in 1992, I had to join politics because people started seeing my father in me,” he says. “Today it is Noor Mahal, not Khas Bagh, that is the seat of the nawabs.”

Referring to Abedi and her brother, historian Shaukat says: “The sister lives in Delhi and the brother in Goa. It is ironic that the direct successors of our nawab have rarely shown interest in the social or political life of Rampur.” This impression is held by more than a dozen people I interviewed in Rampur. The mild-mannered Afroz Khan, a former MLA who is not related to the nawabs but is so popular that everyone in town knows the way to his residence, says: “The State Period was Rampur’s golden era. If Naghat and Murad (Mohammad Ali Khan’s nickname) regularly mingle with the local gentry, they will be loved in the city.”

Confessing that he has not interacted with Rampur society as much as he would have liked, Mohammad says: “After graduating from St Stephen’s in Delhi, I went to San Francisco for my MBA and stayed in the US for 26 years. It was after my mother’s death that I packed up my life in America and returned to India. My love and deep association with the people of Rampur is ever-present and hopefully soon, my presence there will remove all their regrets.”

Born a few days before independence, Abedi is the eldest member of her generation in the family. She lives with her three daughters in central Delhi’s Nizamuddin East. Her staff call her Shehzadi Sahiba, the princess. Showing me black and white photos of her parents, she says: “I spent my growing years in Delhi. We visited Khas Bagh during the holidays. Now I go there once a month and stay for two or three days. It is difficult to maintain things when they are under litigation. In most families where there is money, there are disputes.” A part of her bungalow is rented out to Aishwarya Singh, a royal from the erstwhile state of Churhat, and his wife Devyani Rana, who was engaged to crown prince Dipendra of Nepal, who killed nine members of his family before turning the gun on himself in 2001.

The Rampur nawabs trace their origins to the 17th century, when two Pathan brothers from Afghanistan arrived in Hindustan to serve the Mughals. The adopted grandson of one of the brothers was awarded the title of nawab along with a substantial part of the Rohilkhand region, which included Rampur. In the 1857 uprising, Mohammad Yusuf Ali Khan, the sixth nawab, saved his house from destruction by allying with the British, who annihilated the Mughals in Delhi and the Oudh nawabs in Lucknow.

The next nawab, Kalve Ali Khan, went down in history for initiating Rampur’s celebrated connection with music. He dreamed of setting up a darbar that could match the brilliance of the pre-1857 Oudh court. This was accomplished by his grandson Hamid Ali Khan. In her book Khyal: Creativity Within North India’s Classical Music Tradition, Bonnie C. Wade writes: “Under Nawab Hamid Ali Khan some of India’s greatest musicians practised their art.” They included tabla player Ahmad Jan Thirakwa, sarangi player Bundu Khan, sarod player Fida Hussein Khan, bin player Wazir Khan, and Kathak dancers Acchan Maharaj and Kalka Prasad. In his autobiography My Music, My Life, sitarist Ravi Shankar writes that Wazir Khan, a member of the family of Tansen, was the guru of the nawab himself and “in his seat next to the nawab’s throne, enjoyed a position that was unique at that time.”

Today, Rampur links to art through Bollywood. It is represented in the Lok Sabha by actor Jaya Prada.

Hamid’s son Raza, the last ruling nawab of Rampur, was himself an artiste. His eldest grandchild, Abedi, remembers him performing in front of family members. “He played the khartal (a percussion instrument),” she says. “He composed Hindi poetry. I regret that I did not learn anything from him.” Raza gave ghazal singer Akhtarbai Faizabadi the title of begum. He also presented her with a blue diamond solitaire that she habitually wore on her nose.

It was during his reign that Rampur merged with India and ceased to exist as a state. “My grandfather did not sign the merger agreement under duress,” says Abedi. “He graciously gave up some of his most precious possessions, like his collection of books.”

The Rampur Raza Library stores 2,500 specimens of Islamic calligraphy, 5,000 miniature paintings, 17,000 manuscripts, and 60,000 printed books. The collection includes a seventh century Quran written on parchment and ascribed to Prophet Muhammad’s son-in-law, Hazrat Ali. Another rare book is a Persian translation of Valmiki’s Ramayan, reputedly Aurangzeb’s personal copy. Managed by the Central department of culture, the library is housed in the domed Hamid Manzil in the heart of the old town, a European-style mansion of Italian marble and gold-plated walls.

Before they moved to Khas Bagh, the nawabs ruled from Hamid Manzil’s chandeliered durbar hall. It lies within a fort; the bazaar shops cling to the fort walls. “Today, Azam Khan wants to demolish the historic walls,” says Kazim, referring to the MLA of Rampur town. A minister in the UP government, Azam Khan, known for abrasive speeches delivered with excessive flourish, has been quoted in city newspapers as saying the shops around the fort could be moved to beautify the town. TheIndian Express described him in 2007 as “the Nawab of the Subaltern”. In April, Mail Today called him “a new-age Godfather” who “has edged out the genteel nawabs in their own state”.

Although Azam has renamed roads that were originally named after the nawabs, the nawabs won’t go away that easily. “Long after we lost power, my uncle (Murtaza) and my father (Mickey Mian) determined that just backing a favourite politician was not enough,” says Kazim. “They decided that in each subsequent election one of them should try to have a place in the UP assembly and the other in the Indian Parliament.”

The last time that a member of the nawab family represented Rampur in the Lok Sabha was in 1999, when Mickey Mian’s widow Noor Bano defeated her nearest rival by over 100,000 votes. She lost to Prada in the 2009 election. It was her second consecutive defeat to the actor. “That’s all right,” says Noor Bano at her residence in Delhi. “When I lose an election, I don’t get disappointed with my people. I don’t own them.”

Her son Kazim hasn’t been defeated in the last four assembly elections, though he has changed parties three times during that period. “Being a member of the ruling party helps in getting development work for your constituency,” he says. Trained in architecture at Columbia University, US, Kazim was a regular in Delhi’s party circuit during the late 1980s. This afternoon he is on his way to his constituency, with a gunner sitting on the back seat of his Scorpio. The mud track is lined with poplars. “Look, my constituency is so fertile,” Kazim exclaims. On reaching a village, the Congress MLA is offered fruit, water and a hand fan. Surrounded by turban-wearing men, his eyes are hidden behind black glasses. The talk focuses on the irregular power supply, and the lack of brick roads.

At one time Rampur was considered second only to Kanpur among UP’s most industrialized cities. “We had a cycle factory, a matchbox factory, a textile mill, a dairy plant and many other industries,” former MLA Afroz says. “Thanks to local politics, most have shut down.”

Dining back home in Noor Mahal, Kazim speaks of his renovation plans. “The mosaic on the floor is being replaced by Italian marble. The furniture upholstery is coming from Sita Nanda’s Villa D’Este store (in Delhi). But of course, with its mere 2.5 acres, Noor Mahal will never be as grand as Khas Bagh.”

Abedi’s drawing room in Nizamuddin East is in the basement. The walls of the staircase are covered with photographs of her parents’ wedding. “They were married a year before independence,” she says. “An air strip was especially built to enable the rulers of Gwalior, Dholpur and Patiala to arrive in their private jets. It was the last great celebration witnessed by Rampur before it merged with India.”

Within the grounds of Khas Bagh, walking through the overgrown gardens whose dozen fountains are now hidden in the undergrowth, poet Gulrez looks up at the deserted palace. Suddenly something brushes past him in the unruly grass. He says:

“Ghulam gardishen sooni pari hain muddat se,

Magar parinde subha-o-shaam bolte hain”

(These corridors that teemed with attendants have been lying quiet for a long time,

But the birds can still be heard here in the morning and evening)

The idea of Rampur

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.

58.

59.

60.

61.

62.

63.

64.

65.

66.

67.

68.

69.

70.

71.

73.

74.

75.

Yes! So you were able to salvage the Rampur pics after all,huh? A great article that makes me want to visit the nawabi city again.

wonderful and haunting pictures.

wwaaaaaaaaaaaah bahut ache,Mashaallah.Rab rakha 🙂

Amazing article with tons of details Mayank. What shameful neglect of such magnificent buildings. Somehow, Indians just do not care about these historical structures, old delhi being a case in point. Perhaps we have too much of history.