Exclusive – The Delhi Walla Interviews the Great Emily Dickinson Scholar Professor Cristanne Miller!

On life with Emily Dickinson.

[Photos by Mayank Austen Soofi, except for Cristanne Miller’s portrait]

It’s so-so. The new Apple TV series on poet Emily Dickinson is trying too hard to make her look like a millennial woke modernist. But Dickinson is already too cool for such a makeover.

Watch the series if you like. Watch the recent films, too, on her, though similarly duh.

But also read my exclusive interview with this super-cool Emily Dickinson scholar. Cristanne Miller is a professor of English in the University of Buffalo. The US-based academic has authored several books on the great American poet. Her newest—it won a prestigious award—presented the 19th century poet’s work in such a new way that the book is believed by many to be the most authoritative Emily Dickinson edition.

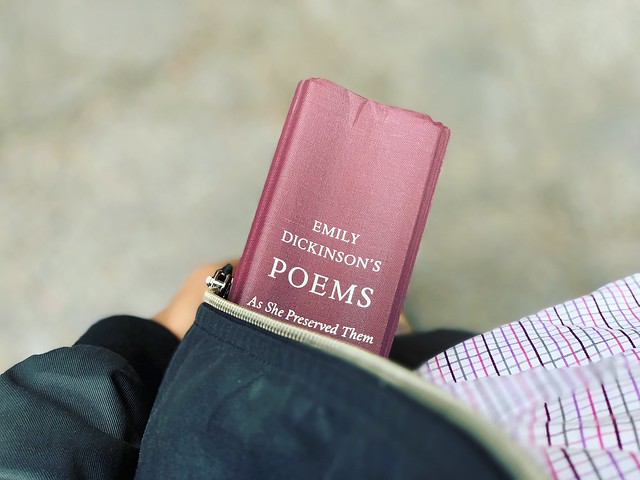

Emily Dickinson’s Poems: As She Preserved Them, edited by Cristanne Miller, was published by Harvard University Press in 2016.

Ms Miller was born in 1953, grew up in Iowa, have lived in many cities, and moved to Buffalo 13 years ago. Her thinking world comprises of Dickinson as well as “nineteenth- and early twentieth-century American poetry, gender and language issues, comparative modernist poetry, the effects of the Civil War on U.S. poetry as a genre, Marianne Moore, Mina Loy, Else Lasker-Schüler, the cities of New York and Berlin between 1900 and 1930, and Civil War poetry.”

Cristanne Miller, a portrait

Ms Miller kindly agreed to talk about Emily Dickinson to The Delhi Walla on e-mail. Thank you, ma’am!

1. How can a person with no academic background but just a passion for words become an Emily Dickinson scholar?

Anyone who loves words can read Dickinson’s poetry with pleasure and with critical understanding. To become a “scholar,” one would need to read the poems but also at least some of the criticism—or pay attention to things like the introductions to the major editions of the poems. There are many independent or self-trained scholars. Greg Mattingly, who recently published Emily Dickinson as a Second Language, is an excellent example.

An Emily Dickinson shelf

2. Can one read all her poems from beginning of the book to the last? Is it wise? Or should Dickinson be read in bits and pieces?

I think one learns different things from reading around in a Dickinson edition and reading an edition straight through—and different editions are arranged in different order. In R. W. Franklin’s 1998 Poems, one would be reading chronologically; in my edition, Emily Dickinson’s Poems: As She Preserved Them (2016), one might read the fascicles in chronological order, and then keep reading straight through or, for example, skip to the poems Dickinson circulated to people and did not retain for herself. They are quite different kinds of poems from the ones in the fascicles! My advice would be to do some of both kinds of reading. Reading her work with attention to chronology and how she is using particular poems (is she binding them into booklets, retaining them in unpolished form, or only mailing and not retaining them) helps you understand how her ideas and style shift over the years in relation to particular audiences. Reading around, however, could make you more alert to the thrill of a particular poem or idea—without attention to her general practice or where the poem occurs in her writing career.

Walking with Emily

3. For a long time Dickinson was portrayed as a heartbroken recluse who wrote poetry in isolation. But now that impression is changing through books, movies and also in a new web series. Can it alter the way a longtime Dickinson reader would respond to her poems?

Yes, I hope that even long-time Dickinson readers will realize that Dickinson was less reclusive than people thought, and that she certainly suffered grief and probably also depression and despair, but that she also articulated repeated joy in living, in her friendships, in nature, and in the pondering of ideas. Some popular representations lean more in one direction and others in the other. She did not circulate the great majority of her poems, but this seems to be because she was in dialogue with herself about these ideas as much as with a general sense of her era, and she was also writing (as most poets do) with an ear for possible future readers. There is no good evidence that Dickinson was “heartbroken,” although there is sufficient proof that she had experienced some form of passionate desire and love. I hope that Dickinson readers will watch these new representations of Dickinson in movies and on the web with a large grain of salt. These representations do not pretend to scholarly objectivity. Some see Dickinson in relation to deeply held convictions of the film-maker; others want to appeal to a new audience for the poems by making Dickinson seem more contemporary, or more “fun.”

Arundhati Roy and Emily Dickinson

4. Do you see enough evidences in your reading that Emily Dickinson was queer? And does her sexuality matter in getting more intimate with her poems?

I do not think we can ever know if Dickinson was actively lesbian. She clearly had passionate and erotic feelings for her sister-in-law, but there is also an established pattern of erotic exchange between women in the 19th century that was regarded as normal for women’s friendship. It is probably not possible for us to know what in Dickinson’s feeling or behavior was a part of this pattern of romantic friendship and what went beyond that norm. (You could look at work by Lilian Faderman on romantic friendship.) She certainly lived somewhere on the spectrum of women loving women, but she seems also to have been capable of deep love for a man (Otis Lord, for example). On the other hand, I do think we can describe Dickinson as “queer” if by that we mean someone who queered or profoundly altered expectations for ways to think about an unmarried woman’s living a rich, fulfilling if also at times deeply troubled life, within a community of people she loves (for Dickinson, primarily but not exclusively her family).

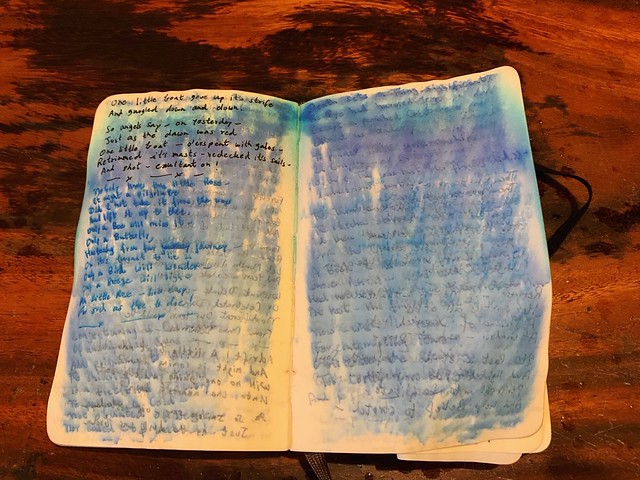

A rain-soaked Emily Dickinson diary

5. Almost all of us are scared about the idea of death. Maybe not of our own but of people we love. Can you talk about if reading Dickinson’s poems—and there are so many of them on death—helps one evolve a less disturbing relationship with death?

This is a very interesting question! Dickinson wrestles more honestly and more profoundly than any writer I know with the question of what happens to us when we die, and she does not come to any definitive answers to her own questions. In fact, she provides contradictory responses, in part because she asks different kinds of questions about death, immortality, and heaven, in different poems. Because she does not have a conventional Christian faith, the conventional answers about “heaven” do not satisfy her. “This World is not conclusion.” she writes—ending that first line of her poem with a period or full-stop; but we will forever be tormented by our doubts as to whether this is true, she goes on to say. Doubt is inextricable from faith. Dickinson also repeatedly wrote that heaven is what we experience on earth, or what we desire but can’t obtain: “’Heaven’ – is what I cannot reach.” In her thinking, we die into some form of extended consciousness: we cannot “see to see” but we do still in some sense “see,” without the eyes of our body. She does not fear death. Life, she tells us, is more painful; it contains greater anguish. Death may even be a comfort (she describes “Time” as “Indignant – that the Joy was come –” in one poem about dying) in that it brings us into the community of those who have already died—but she has no sense of what that actually means. Her greatest poems and letters of consolation are not for those suffering illness preceding death but for the living who suffer grief, when a beloved spouse, family member, or friend dies.

Bonding with Emily

6. How has a lifetime of reading Emily Dickinson altered the way you perceive your world?

Dickinson has been a part of my thinking for so long that I cannot answer that question. I have been reading her seriously since I was in my early twenties. It does not seem to me that reading her radically altered any way of living or thinking for me, but that’s so long ago, and I was then so young, that I can’t tell.

Emily in many tongues

7. Dickinson is noted for her thousands of letters, too. If her sister had failed to chance upon the trunk of poems in Emily’s room after her death, would Dickinson’s letters alone ensure her a high place in literature?

Dickinson’s letters are remarkable, but I do not think that they alone would ensure her status as a great writer—unless perhaps you counted the around 500 poems she also circulated (out of the almost 1800 for which copies survive). Still, the most frequently anthologized and cited poems are among those that (to our knowledge) she never circulated. These include “Because I could not stop for Death –”, “I felt a Funeral in my Brain,” “After great pain, a formal feeling comes –”, “This World is not conclusion.”, “Come slowly – Eden!”, “Wild nights – Wild nights!”, “I can wade Grief –”, “The Spider holds a Silver Ball,” and many others. The letters fascinate in part because they bring us closer to the writer of the poems. (And I say this while working on a new edition of the letters, together with Domhnall Mitchell.)

An intimacy with Emily

8. Your poetry collection on Emily Dickinson is path-breaking in the way one tackles this poet. It’s an edition that a true Emily Dickinson lover is obliged to carry in his/her shoulder bag all the time. But why did your publishers make it so heavy, unusual even in the context of the hardbound? When can we expect a paperback?

My editor at Harvard University Press tells me that she is working to get Emily Dickinson’s Poems: As She Preserved Them on the list for paperback publication. I do not have a date when it will occur, but I hope that it will be within the next year or two.

Thank you, Ms Miller.

Wearing Emily’s garden

Lounging with Emily

Emily’s bookmarks

Emily Dickinson, always

Recent Comments